Health correspondent in Africa, Lagos

Gety pictures

Gety picturesAt the age of twenty -four, Navisa Salaho was at risk of becoming another census in Nigeria, where a woman died every seven minutes, on average.

Entering labor during the doctors’ strike means that although he was in the hospital, there was no help at hand as soon as complications appeared.

Her baby’s head was stuck and was only said to lie during labor, which lasted for three days.

Ultimately, Caesarea was recommended and there was a doctor who was ready to implement it.

“I thanked God for almost dying. I had no power, I had nothing remaining,” Mrs. Salah BBC of Cano is in the north of the country.

She survived, but her child died tragicly.

After 11 years, she returned to the hospital to generate several times and takes a fatal position. “I knew (every time) between life and death, but I am no longer afraid,” she says.

The experience of Mrs. Salaho is not unusual.

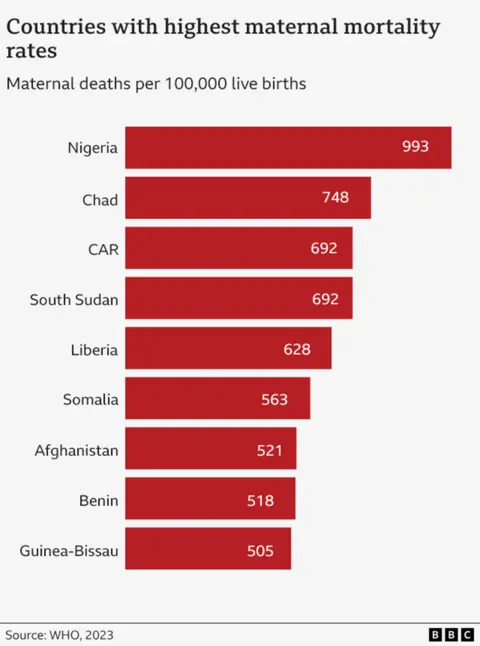

Nigeria is the most dangerous nation in the world in which it gives birth.

According to The latest United Nations estimates for the countryThey were collected from 2023 numbers, one in every 100 women die in labor or the following days.

This places it at the top of the league table, there is no country that wants to head it.

In 2023, Nigeria formed more than a quarter – 29 % – from all maternal deaths around the world.

This is a total of 75,000 women who die in birth in one year, which works on one death every seven minutes.

Warning: This article contains a picture of a newly born baby.

Henry Edda

Henry EddaFor many frustration is that a large number of deaths – of things like after birth (known as postpartum bleeding) can be prevented.

Shinini Nuiz was thirty -six years old when she blew up to death in a hospital in the southeastern town of UNicha five years ago.

“Doctors need blood.”. “The blood did not have enough and they were running. The loss of my sister and my friend is not something I wish for the enemy. The pain is unbearable.”

Among the other common causes of mother deaths are obstruction, high blood pressure and unsafe abortion.

The “very high” mothers’ mortality rate in Nigeria is the result of a group of factors, according to Martin Dolston of the Nigeria Office of the United Nations Children’s Organization, UNICEF.

Among them, he says, weak health infrastructure, lack of paramedics, expensive treatments that many cannot tolerate, and cultural practices that can lead to some medical professionals and insecurity.

“There is no woman who deserves to die during a child’s nomination,” says Mabel Onoimina, the National Women’s Coordinator in the Development of the purpose.

She explains that some women, especially in rural areas, believe that “visiting hospitals is a complete waste of time” and choosing “traditional treatments instead of seeking medical help, which can delay life -saving care.”

For some, access to the hospital or clinic is almost due due to the lack of transportation, but Mrs. ONWuemena believes that even if they can, their problems will not end.

“Many health care facilities lack basic equipment, supplies and trained employees, making it difficult to provide high quality service.”

The Nigerian federal government is currently spending only 5 % of its health budget – less than the 15 % goal that the country has adhered to in the 2001 African Union Treaty.

In 2021, there were 121,000 midwives of a population of 218 million and less than half of all births, supervised by a skilled health worker. It is estimated that the country needs 700,000 nurses and other midwives to meet the recommended global health organization.

There is also a severe shortage of doctors.

The lack of employees and facilities puts some of the pursuit of professional assistance.

“Frankly, I do not trust hospitals a lot. There are many neglect stories, especially in public hospitals,” says Gillla Isaac.

“For example, when I gave birth to my fourth child, there were complications during labor. We advised the local birth host to go to the hospital, but when we got there, there was no health care worker to help me. I had to go home, and this is where we eventually gave birth to.”

The 28 -year -old girl from Kano’s state is now expecting her fifth child.

She adds that she will consider going to a private clinic, but the cost is high.

Chinundo Obegeisi, who expects her third child, is able to pay the hospital’s private health care price and “you will not think about birth anywhere.”

She says she is among her friends and family, the mother’s deaths are now rare, while she used to hear a lot about her.

She lives in one of the wealthy suburbs of Abuja, where he is easy to access hospitals, the roads are better, and to make emergency services. Also, more women in the city learn and know the importance of going to the hospital.

“I always bring prenatal care … I am allowed to speak with doctors regularly, do important tests and survey, and follow both my health and child,” Mrs. Obigisi BBC told Mrs. Obigisi BBC.

“For example, during the second pregnancy, they expected to bleed severely, so they prepared additional blood in the case of blood transfusion. Fortunately, I didn’t need it, and everything walked well.”

However, a family friend was not very lucky.

During her second work, “the birth hostess was unable to deliver the child and tried to force him to go out. The child died. Under the time she was transferred to the hospital, it was too late. She still had to undergo surgery to deliver the child’s body. It was shattered.”

Gety pictures

Gety picturesDr. Nana Sandah Abu Babel, Director of Community Health Services at the National Primary Health Care Development Agency in the country (NPHCDA), admits that the situation is comfortable, but he says that there is a new plan that is developed to address some issues.

Last November, the Nigerian government launched the experimental phase of the initiative to create mothers’ deaths (MAMII). In the end, this will target 172 local government zones in 33 states, which represent more than half of the births related to the country.

“We define every pregnant woman, know where she lives, and we support her through pregnancy, childbirth and beyond.”

Until now, 400,000 pregnant women have been found in six states in a poll from house to house, “with details if they are attending Natal (chapters) or not.”

“The plan is to start linking them to services to ensure that they get care (they need) and that they provide safely.”

Mamii will aim to work with local transportation networks to try to get more women to clinics and also encourage people to participate in low -cost public health insurance.

It is too early to say whether this has any effect, but the authorities hope that the country can follow the direction of the rest of the world in the end.

Globally, the mother’s deaths decreased by 40 % since 2000, thanks to the expanded access to health care. The numbers also improved in Nigeria during the same period – but by only 13 %.

Despite Mamii, and other programs, being welcome initiatives, some experts believe more – including more investment.

“Their success is dependent on continuous financing, effective implementation and continuous monitoring to ensure the achievement of the intended results,” says Mr. Dolkin from UNICEF.

Meanwhile, the loss of every mother in Nigeria – 200 every day – will remain a tragedy for the families concerned.

For Mr. Ida, the sadness of losing his sister is still raw.

He says: “I went up to become our anchor and our spine because we lost our parents when we grew up.”

“On my only time, when I cross my mind. I cry bitterly.”

More BBC stories from Nigeria:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/7d0b/live/96b16cb0-3c6c-11f0-aa24-d1c64c46ace6.jpg

Source link