BBC News

BBC

BBCEvery morning, Rosa Qhamami wakes up on fire to lick the cardboard scraps in a temporary stove in its courtyard.

The boxes that I brought to the home once held 800,000 high -tech solar panels. Now, they feed the fire.

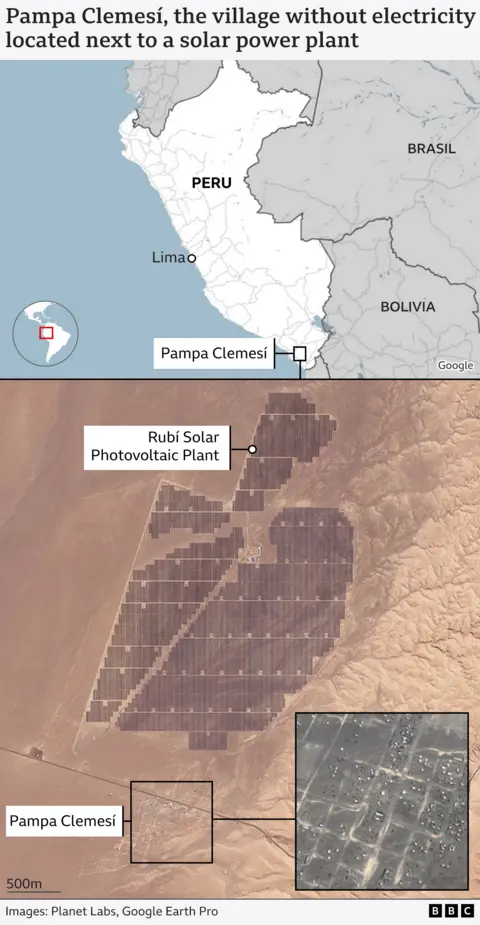

Between 2018 and 2024, these paintings were installed in Ruby and Clemessi, two huge solar factories in the Moquegua area in Peru, about 1000 km south of the capital, Lima. Together, it is the largest solar complex in the country – and one of the largest complexes in Latin America.

From her home in the small settlement of Bamba Clemery, Rosa can see the rows of glowing panels under the white spotlight. Ruby is only 600 meters.

However, her home – and the rest of her village – still in complete darkness, is not connected to the network on which the plant feeds.

Sun strength, but not at home

None of Pampa Clemesí 150 can access the national energy network.

There are a few of the solar panels donated by the Ruby operator, Organ, but most of them cannot afford the costs of the batteries and transformers needed to make them work. At night, they use torches – or simply live in the dark.

The paradox is striking: The Rubí Solar Station produces about 440 GB, which is enough to provide electricity to 351,000 homes. Moquueugua, where the factory is an ideal location for solar energy, receives more than 3,200 hours of sunlight annually, more than most countries.

This contradiction becomes more clear in a country currently witnessing a renewed energy boom.

In 2024 alone, electricity generation from renewable energy sources grew by 96 %. Solar energy and wind depends greatly on copper due to high conductivity-Peru is the second largest producer in the world.

“In Peru, the system was designed about profitability. No effort was made to connect the populated areas,” explains Carlos Gordello, an energy expert at the University of Santa Maria in Arikiba.

Organ says she has fulfilled her responsibilities.

“We have joined the government project to bring electricity to Pamba Clemery, and we have already built a designated line for them,” said Marco Fragale, CEO of Peru News Mondo. We have also completed the first phase of the electricity project, with 53 power generation tower. “

Fragale adds that approximately 4000 meters of underground cables have been installed to provide the village’s power line. He says the investment of $ 800,000 is complete.

But the lights still did not come.

The last step – linking the new line with individual homes – is the responsibility of the government. According to the plan, the Ministry of Mines and Energy must have about a kilometer of wires. The work was scheduled to start in March 2025, but it did not start.

BBC News Mondo tried to contact the Ministry of Mines and Energy, but he did not receive any response.

A daily conflict for the basics

Rosa’s little house has no sockets.

Every day, she walks around the village, hoping that someone can provide a little electricity to charge its phone.

“It is necessary,” she says, explaining that she needs to stay in contact with her family near the border with Bolivia.

One of the few people who can help is Rubén Pongo. In his larger home – with the courtyards and many rooms – a group of chickens battles for space on the surface between the solar panels.

“The company donated solar panels for most villagers,” he says. “But I had to buy a battery, transformer and cables myself – and pay the price of the installation.”

Robin has something that others dream only: a refrigerator. But it only works for up to 10 hours a day, in cloudy days, not at all.

It helped build the Rubí and later worked in maintenance, cleaning the panels. Today, the warehouse runs and leads the company to work, although the factory is located across the road.

It is prohibited to cross the Americans on foot under Peruvian law.

From its surface, Rubin refers to a group of incandescent buildings in the distance.

“This is the sub -station of the plant,” he says. “It looks like a small liter city.”

long standing

The residents began to settle in Pamba Clemery in the early first decade of the twentieth century. Among them is 70 -year -old, Pedro Chara. The Ruby Factory has seen 500,000 paintings rising almost on the threshold of his torque.

A large part of the village was built of neglected materials of the factory. Pedro says even their family comes from scrap wood.

There is no water system, water, no set of garbage. The village was once 500 people, but because of the rare infrastructure, the majority-especially during the Covid-19 pandemic left.

He says: “Sometimes, after waiting for a long time, you fight for water and electricity, you feel like you are dying. That’s all. Death.”

Dinner from Torchlight

Rosa accelerated to her aunt’s home, hoping to take the last daylight. Tonight, she cooks dinner for a small group of neighbors who share meals.

In the kitchen, the gas stove is heated. Their only light is a solar powered flame. Dinner is sweet tea and fried dough.

“We only eat what we can keep at room temperature,” says Rosa.

Without cooling, it is difficult to store protein -rich foods.

Fresh products require a 40-minute bus riding to Moquegua- if they can bear their costs.

“But we have no money to take the bus every day.”

With no electricity, many cook in Latin America with firewood or kerosene, and they risk respiratory diseases.

In Pampa Clemery, the population uses gas when they can withstand its costs – wood when they cannot.

They pray through Torchlight for food, shelter and water, and then eat silently. It is 7 pm, their final activity. No phones. No TV.

“Our only light is these little torches,” says Rosa. “They don’t show much, but at least we can see the bed.”

“If we have electricity, people will return,” says Pedro. “We stayed because we had no choice. But with light, we can build a future.”

A soft breeze that provokes the streets of the desert, and the sand lifting. A layer of dust settles on Lampposts on the main arena, awaiting its installation. Wind signals coming dusk – this is close, there will be no light.

For those who do not have solar panels, such as Rosa and Pedro, darkness extends to sunrise. Likewise, they hope that the government will behave one day.

Like many nights before, they prepare for another evening without light.

But why are they still living here?

“Because of the sun,” Rosa responds without hesitation.

“Here, we always have the sun.”

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/eecd/live/06dbdfb0-617b-11f0-960d-e9f1088a89fe.jpg

Source link