Zambia History Museum

Zambia History MuseumWooden Fishermen Tools included in the old writing system from Zambia making waves on social media.

“We have grown up, as he told us that Africans do not know how to read and write,” says Samba Yonga, one of the founders of the Virtual Women’s History Museum in Zambia.

“But we had our own way of writing and transferring knowledge that was completely lined and ignored,” I told the BBC.

It was one of the handicrafts that launched a campaign on the Internet to highlight the roles of women in societies before colonialism – and to revive the cultural heritage that was almost wiped by colonialism.

Another interesting object is a complexly decorated leather cloak that has not been seen in Zambia for more than 100 years.

“Handicrafts refer to an important date – and an unknown history,” says Yonga.

“Our relationship with our cultural heritage has been disrupted and withheld through the colonial experience.

“It is also shocking how long the role of women has been removed.”

Zambia History Museum

Zambia History MuseumHowever, Yonga says: “There is a return, need and hunger to communicate with our cultural heritage – and to restore from us, whether through fashion, music or academic studies.”

“We had our own language of love and beauty,” she says. “We had ways to take care of our health and our environment. We had prosperity, union, respect and thought.”

A total of 50 creatures have been published on social media – Besides information about its importance and goal, which indicates that women were often at the heart of the systems of society’s beliefs and understanding the natural world.

Images of objects are presented within the frame – playing on the idea that the ocean can affect how you view and perceive. In the same way that British colonialism has distorted the history of Zambian – by silencing and destroying local wisdom and practices.

The framework project uses social media to decline against an idea that is still common. African societies did not have their own knowledge systems.

Things were mostly collected during the colonial era and kept storage in museums all over the world, including Sweden – where this current project’s journey began on social media in 2019.

Yonga was visiting the capital, Stockholm, and her boyfriend suggested that she meet Michael Barrett, a coordinator National Museums of International Cultures in Sweden.

She did – and when he asked her about the country from which she was, Yonga was surprised by his hearing saying that the museum had a lot of Zambian artifacts.

“I truly detonated my opinion, so I asked:” How was there a country that had no colonial past in Zambia a lot of artifacts from Zambia in its group? “

In the nineteenth and early twentieth century, the Swedish explorers pay ethnography and plant scientists to travel on British ships to Cape Town, then make their way with railways and foot.

There are approximately 650 Zambian cultural body in the museum, collected over a century – as well as about 300 historical pictures.

Zambia History Museum

Zambia History MuseumWhen Yonga and her co -founder of her museum, Mollinga Capoepoy, explored the archives, they were surprised to find the Swedish collectors who traveled widely – some artifacts come from areas in Zambia that are still far and difficult to reach.

The group includes cane fishing baskets, festive masks, utensils, and waist belt belt – and 20 leather gowns in a rudimentary state collected during the 1911-1912 trip.

It is made of Lechwe skin by Batwa men and women wears or women use them to protect their children from elements.

Yonga says that “engineering patterns” are geometric patterns, accurately, accurate and beautiful.

There are pictures of women who wear gowns, and a 300 -page laptop written by the person who brought gowns to Sweden – Eric Van Rosen.

He also painted illustrations that show how gowns were designed and pictures of women who wear gowns in different ways.

“I face great pain to show the cloak that is designed, all the angles and tools that were used, (geography) and the location of the region from which it came.”

The Swedish Museum did not have any research on gowns – and the National Museum Council in Zambia was not aware that they were present.

So Yonga and Capoepoy went to discover more society in the Bengoyo region in the northeast of the country, where gowns came.

“There is no memory for her,” says Yonga. “Everyone who keeps this knowledge of the creation of this special fabric – that leather cloak – or understood that history is no longer there.

“So it was only present at this frozen time, in this Swedish Museum.”

Zambia History Museum

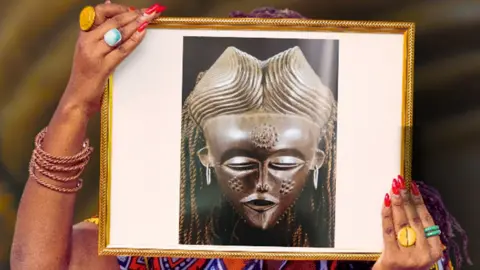

Zambia History MuseumOne of Yonga’s personal favorites in the Frame project is Sona or Tusona, an old and sophisticated writing system and is rarely used now.

It comes from Shokoy, Luzhazi and Lovil, who live in the border in Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the northwestern region of Yonga.

Engineering patterns were made in the sand, on the fabric and on the bodies of people. Or carved in furniture, wooden masks used in Makishi Ancestral MASQUERAEDE – and a wooden box used to store tools when people were out of hunting.

The patterns and symbols bear mathematical principles, references to the universe, and messages about nature and the environment – as well as instructions on society’s life.

The guardians and the original women of the women were women – and there are still community elders remembering how it works.

It is a great source of knowledge of Yonga’s continuous influence of research conducted by scientists such as Marcus Matt Wolus Gerdes.

“Sona was one of the most popular social media posts – with people expressing huge surprise and excitement, crying:” Like, what, how is this possible? “

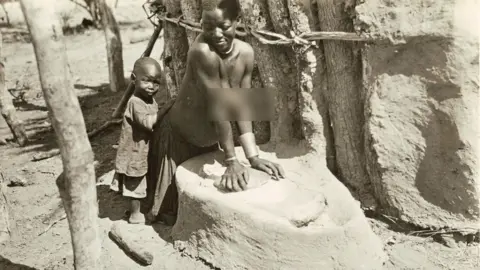

Queens in the code: Power Power Women’s symbols include a picture of a woman from the Tonga community in southern Zambia.

She has her hands on a meal grinder, a stone used to grind grain.

National Museums of Global Cultures

National Museums of Global CulturesResearchers from the Women’s History Museum in Zambia discovered during a field trip that the grinding stone was more than just a kitchen tool.

He only belonged to the woman she used – she was not transferred to her daughters. Instead, she was placed on her grave as a grave in respect of the contribution that the woman made to the food security of society.

“What may seem just grinding stone is actually a symbol of a woman’s strength,” says Yonga.

The Women’s History Museum was established in Zambia in 2016 To document and archive the history of women and original knowledge.

It is conducting research in societies and creating an online archive for the elements that were removed from Zambia.

“We are trying to assemble a panorama without having all the pieces yet – we are hunting the treasure.”

Hustle the treasure that changed the life of Yonga – in a way that the social framework project hopes to also do other people.

“I have a sense of my community and an understanding of the context of I am historically, politically, socially, emotionally – may change the way I interact in the world.”

Benny del is an independent journalist, podcast maker and documentary -based documentary maker

More BBC stories on Zambia:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/5d41/live/f38f9be0-43fc-11f0-835b-310c7b938e84.jpg

Source link