Mexico, Central America and Cuba correspondent

BBC

BBCAfter the thirtieth month in a row without rain, the residents of the town of San Francisco de Konchos gather in the northern Mexican state of Chihuwa to defend divine intervention.

On the beaches of Lake Toronto, the tank behind the most important dam in the state – is called La Boquilla, the priest of local farmers leads to horse and their families in prayer, and the rocky land under their feet as soon as the water drops to low levels today.

Among those who have their heads, Rafael Betynnes, who voluntarily monitored not Bookilla for the power of state water for 35 years.

“All this should be under water,” he says, and he is heading towards the geographical extension of the exposed white rocks.

“The last time the dam was full and caused a small surplus in 2017,” says Mr. Betanns. “Since then, a year has decreased on an annual basis.

“We are currently 26.52 meters under the high water mark, less than 14 % of its ability.”

No wonder that the local community spoils the sky to rain. However, the few do not expect any leaving from the disrupted dehydration and heat 42C (107.6F).

Now, a long -term conflict with Texas over the rare resource threatens the ugly shift.

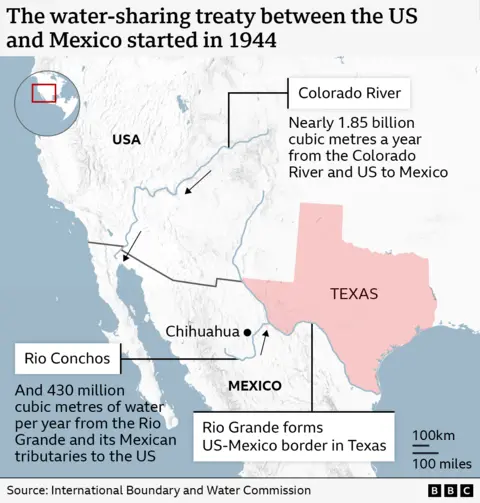

Under the conditions of the water sharing agreement in 1944, Mexico must send 430 million cubic meters of water annually from Rio Grande to the United States.

Water is sent via a system of tributaries to the common dams owned by the Border and International Water Committee (IBWC), which oversees and regulates water exchange between neighbors.

On the other hand, the United States sends a much larger allocation (approximately 1.85 billion cubic meters per year) from the Colorado River to supply the Mexican border Tijuana and Mexical border cities.

Mexico is late and failed to keep up with water connections in most of the twenty -first century.

After pressing the Republican lawmakers in Texas, the Trump administration warned Mexico that water can be blocked from the Colorado River unless it fulfills its obligations under the 81 -year -old treaty.

In April, on his social account, US President Donald Trump accused Mexico of “stealing” water and threatened to continue the escalation to “customs tariffs, and perhaps even sanctions” until Mexico sends Texas what you condemn. However, no fixed deadline was given through this revenge.

For its part, the Mexican President, Claudia Shinbom, admitted to Mexico, but it struck a more reconciliation tone.

Since then, Mexico has moved 75 million cubic meters of water to the United States through its joint dam, Amistad, located along the border, but this is just a small part of about 1.5 billion cubic meters of hanging Mexico debts.

Feelings on the sharing of the cross -border water can be dangerously high: in September 2020, two Mexican people were killed in clashes with the National Guard in the La Boquilla gates, while farmers tried to prevent water from redirect.

In the midst of acute drought, the prevailing opinion of Chihuahua is that “you cannot take from what is not there,” says local expert Rafael Betance.

But this does not help Brian Jones watering his crops.

Only the fourth generation farms in the Rio Grande Valley in Texas, over the past three years, were able only to grow half of his farm because he does not have enough irrigation water.

“We were fighting Mexico because they did not reside to the level of the deal,” he says. “All we ask is really in the framework of the treaty, nothing is additional.”

Mr. Jones also ignores the problem with Chihuwa. He believes that in October 2022, the country received more than enough to participate, but it was “completely zero” to the United States, accusing his neighbors of “storing water and using them to develop crops to compete with us.”

Farmers read on the Mexican side the agreement differently. They say it only connects them by sending water north when Mexico can meet its own needs, and they argue that the continuous drought of Chihuahua means that there is no surplus available.

Outside of water scarcity, there are also arguments about agricultural efficiency.

Walnut and alfalfa trees are one of the main crops in the Rio Konchos Valley in Chihuwa, both of which require a lot of walnut on average 250 liters per day.

Traditionally, Mexican farmers simply flooded their fields with water from the irrigation channel. He drives his car around the valley soon sees walnut trees sitting in shallow pools, and water flows from an open tube.

The complaint of Texas is clear: This practice is a waste and easy to avoid with the most responsibility and sustainable cultivation methods.

While Jaemy Ramirez is going through walnut orchids, the mayor of San Francisco de Konchos explains to me how the modern sprinkler system guarantees that the walnut trees are properly watering throughout the year without wasting the precious resource.

“With machine guns, we use about 60 % of the dumping of fields,” he says. The system also means that they can water the trees frequently less, which is especially useful when the Conchos Rio is very low so that it is not allowed for local irrigation.

Mr. Ramirez easily admits that some of his neighbors are not conscience. As a former local mayor, urges understanding.

He says that some did not adopt the spraying method due to the costs in preparing it. He has tried to show other farmers that he works for long -term cheaper, providing energy and water costs.

But farmers in Texas must also understand that their counterparts in Chihuwa are facing an existential threat, Mr. Ramirez insists.

“This is a desert area and the rain does not come. If the rain does not come again this year, there will be no simply any cultivation. All available water should be preserved as drinking water for humans,” he warns.

Many in northern Mexico believe that the 1944 water participation treaty is no longer suitable for the purpose. Mr. Ramirez believes that he may have been sufficient for eight decades ago, but he failed to adapt to times or calculate population growth properly or climate change scourge.

Again across the border, the Texas Brian Jones farms say the agreement had withstood the test of time and must be honored.

“This treaty was signed when my grandfather was grown. My grandfather and my father passed and now I am.”

“Now we see Mexico does not comply. It is very angry that you have a farm where I can only grow half of the ground because I do not have irrigation water.”

He adds that Trump’s most striking position gave local farmers “Pep in our step.”

Meanwhile, drought did not harm the cultivation in Chihua.

With the low levels of Lake Toronto, Mr. Betance says that the remaining water in the tank is heating at an unfamiliar speed and creating a possible marine life disaster that once maintains the tourism industry.

Mr. Betance says that the Valley’s view was not, for the course of time, carefully spent the rise and landing in the lake. “Prayer for rain is all that we left,” he says.

Additional reports by Angelika Casas.

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/f5ad/live/dc1179a0-58d0-11f0-a113-db0360eed65c.jpg

Source link