BBC World Service

Gety pictures

Gety picturesPakistan deported more than 19,500 Afghans this month, among more than 80,000 who left before the deadline on April 30, according to the United Nations.

Pakistan has accelerated its engine to expel the unconventional Afghans and those who have a temporary permission to survive, saying that it could no longer overcome.

Taliban officials say between 700 and 800 families per day, Taliban officials say, as it is expected to follow up to two million people in the coming months.

Pakistani Foreign Minister, Isaac, Dar, flew to Kabul on Saturday for talks with Taliban officials. His counterpart, Amir Khan, has expressed “deep concern” about the deportation.

Some Afghan said on the border that they were born in Pakistan after their families fled from the conflict.

More than 3.5 million Afghans live in Pakistan, according to the United Nations Refugee Agency, including about 700,000 people who came after the Taliban acquired in 2021. The United Nations estimates that the half is not documented.

Pakistan has taken Afghans through decades of war, but the government says that the large number of refugees are now risks to national security and cause pressure on public services.

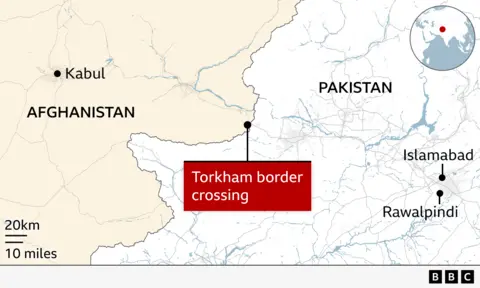

There was a recent rise in the border clashes between the security forces of both sides. Pakistan blames them for gunmen based in Afghanistan, which is denied by the Taliban.

The Pakistani Ministry of Foreign Affairs said that the two sides “discussed all issues of mutual attention” at a meeting on Saturday in Kabul.

Pakistan has extended a final date for the unconfirmed Afghans to leave the country for a month, until April 30.

At the Torkham Border crossing, he told some of the Afghans away from the BBC that they left Afghanistan decades ago – or never lived there.

“I lived my whole life in Pakistan,” said Sayyid Al -Rahman, a refugee of the second generation of refugees born in Pakistan. “I got married there. What are I supposed to do now?”

He asked, the father of three daughters, who is concerned about what life means in light of the Taliban’s rule for them. His daughters attended the school in Pakistan Punjab province, but in Afghanistan, girls are prevented over the age of 12.

“I want to study my children. I don’t want to waste their years at school,” he said. “Everyone has the right to education.”

Another BBC told: “Our children have never seen Afghanistan, and so I don’t know what it looks after it. It may take a year or more to settle and find work. We are unable.”

On the border, men and women pass through separate doors, under the observation of the armed Pakistani guards and Afghans. Some of the returnees were the elderly – a man was transferred to a stretch, and another in bed.

Military trucks transferred families from the border to temporary shelters. This remains originally from the distant provinces there for several days, pending transportation to their household areas.

Families were assembled under the panels to escape from a temperature of 30 ° C, where dust was caught in the eyes and mouth. Resources are extended and fierce arguments are often exploding.

Obtaining between 4000 and 10,000 Afghans (41 pounds to 104 pounds) from Kabul authority, according to Hilayataling to Heidelle Xinwari, a member of the financing committee that was filled in the camp.

The mass deportation puts great pressure on the fragile infrastructure in Afghanistan, with an economy in the crisis and their population reaches 45 million.

“We have resolved most of the issues, but people reach these large numbers naturally bring difficulties,” said Bakht Jamal Jamar, Chief of Refugees at the Taliban at the crossing. “These people have left decades ago and left all their possessions behind them. Some of their homes were destroyed in 20 years of war.”

Almost every BBC has told the Pakistani border guards to restrict what they could filed – a complaint that some human rights groups have been reported.

“It has no policy that prevents Afghan refugees from taking home tools with them.”

A man, sitting on the side of the road in strong sunlight, said that his children had begun to stay in Pakistan, the country where they were born. They have been given temporary stay, but this ended in March.

“Now we will never come back. Not yet how we are dealing,” he said.

Participated in additional reports from Daniel Vittenberg and Malorer Minch

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/3643/live/2a79eca0-1d2e-11f0-b1b3-7358f8d35a35.jpg

Source link