Canadian researchers say they should stop providing children with cancer places in some clinical trials due to financing and political changes in the United States.

The United States government stops financing some clinical trials for children outside the United States, and the lack of funding for the funding of the children’s tumor union, a network of experts that conduct clinical trials and focus on improving brain tumor treatments.

The only Canadian website is located in the network at the Toronto Hospital for infants.

Dr. Jim Whitig, head of the C17 Council, who represents children’s cancer programs in Canada, and head of the hematology/oncology department in sick children, said they should stop registering new patients in three clinical trials due to change. Current patients can continue to receive treatments.

The United States government does not renew the funding of the Children’s brain tumor union, a network of experts focusing on improving brain tumor treatments, and Sickkids Hospital in Toronto had to stop registration of children in some new experiences as a result.

“These are some promising treatments for children who suffer from these specific diseases, and there are no studies on the equivalent promise that we can reach,” Whitig said.

The US National Health Institutes, the responsible agency, said that the work of a consortium will move to another network that also has sites in Canada – but it is facing freezing on financing experiments outside the United States

This network, which is the clinical trial network in the early stage of children (Pep-CTN), contains two Canadian sites, one in Sick Kids and another at Chu Sainte-Justine for Children in Montreal.

“This change is concerned,” said Dr. Tae Hua Tran, medical director of Pep-CTN in Canada.

Tran says two clinical experiences of children’s cancer have stopped recording patients due to freezing.

“The message we received is that the registration has stopped for Canadian children,” said Tran.

In a statement by CBC News, Elizabeth Fox, President of Pep-CTN, said that the network learned in August that although its general financing continued, the financing of non-American sites was suspended, and the registration was stopped for new patients outside the United States.

Clinical experiments can be the last option

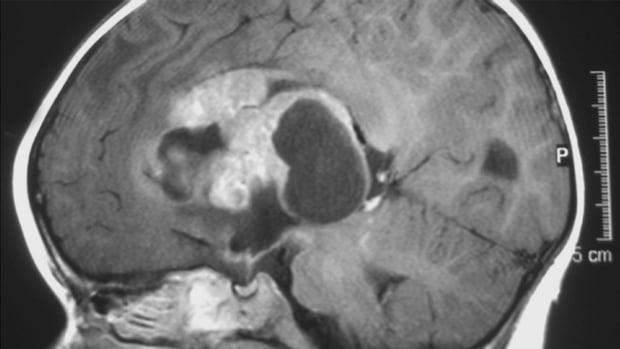

Child cancer is rare, with about 1,000 children under 15 years old Diagnosis in Canada every year. While most of them respond well to treatment, it does not do everything. In these cases, clinical trials can be a last option, says Dr. Sheila Singh, children’s neurosurgery at McMaster University.

She said: “Often with brain cancer in children, we have reached a point that can no longer be treated with standard therapeutic methods and the only hope for these children is to search for an experimental treatment.”

Clinical experiments are for the most difficult treatment, so the number of children with children is small, but Singh says that loss of access to experiments is still a great loss for potential patients and future research.

She said: “We had already been a guest who was suffering from difficulty in treating brain cancers that could be treated and that could have been eligible to get one of those experiments,” she said.

“But now these experiments have been closed, and therefore we cannot provide experimental treatment options full of hope and promising.”

Patient perspective

When it comes to child cancer, there is no easy decision for parents.

When Ibn McCainch was diagnosed with brain cancer at the age of nine, he underwent surgery, proton radiation and chemotherapy. He is now seventeen years old and graduates from high school in Ottawa.

After treatment, he also participated in a clinical trial, and a drug test to help the brain recover.

McCainteh says he is worried about the loss of other children to reach similar opportunities.

“Loss of any option provides an opportunity to treat or benefit a meaningful … it can be destroyed,” he said.

Three -year -old Emit Doulan’s parents learned that she had an aggressive brain tumor just days after her birth.

Chemotherapy began at the age of three weeks and shortly after joining a clinical trial at BC Children’s Hospital for a treatment of its specified type of tumor. The oral administration of the drug allowed it to be treated in its home community in the village of Kitamaa.

“It was the best thing for her ever.”

“With all the harsh side effects with chemotherapy, I don’t think it would continue this long,” she said.

Canada should enhance capacity

Given continuous financing and political changes in US health care under the Trump administration, the researchers say that Canada must enhance its ability to do more clinical experiences here.

“We need the federal government to help break down barriers that impede the behavior of effective clinical trials in Canada,” said Dr. BJ Daviro, cardiologist and professor at McMaster University.

“We are a very complex and cost -effective place to conduct research,” said Cathy Buddor Rob, Executive Director of the C17 Council.

She says that this country needs to put itself to be less dependent on the United States

“Canada needs to collect its work together.”

“Through recent changes and politics in the United States, this was a difficult and worrying time for the research community,” said Canadian Health Research

The National Health Institutes said that it will succeed in finding ways for Canadian institutions to register in the clinical trials in the future, as soon as the transition is complete.

https://i.cbc.ca/1.7636826.1758154287!/fileImage/httpImage/image.jpg_gen/derivatives/16x9_1180/dr-sheila-singh.jpg?im=Resize%3D620

Source link