BBC News, London

British Museum Secretaries

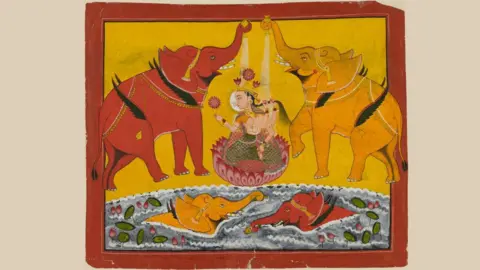

British Museum SecretariesA new exhibition at the British Museum in London displays the rich journey of India’s spiritual art. Entitled “Old India: Live Traditions, 189 wonderful things that extend for centuries.

Visitors can explore everything from 2000 -year -old sculptures and paintings to complex narrative panels and manuscripts, revealing the amazing development of spiritual expression in India.

Art of the Indian subcontinent was subjected to a deep transformation between 200BC and 600 AD600. The images depicting the gods, gods, supreme preachers and enlightened spirits of three ancient religions – Hindu, Buddhism and Leniki – were re -imagined from symbolism to more extracted than the human form.

While the three religions participated in the common cultural roots – worship the souls of ancient nature such as strong snakes or peacock feelings – they negotiated the dramatic transformations in religious icons during this central period that is still contemporary with thousands of millennials.

“Today we cannot imagine the veil of Hinduism, Jain, divine spirits, or Buddhist gods without a human form, can we? What makes this transition interesting,” says Sushma Yansari, Secretary of the Exhibition.

The exhibition explores both the continuity and change in sacred art in India through five sections, from the spirits of nature, followed by the sub -sections allocated to both religions, and concludes with the spread of religions and their art beyond India to other parts of the world such as Cambodia and China.

British Museum Secretaries

British Museum Secretaries British Museum Secretaries

British Museum SecretariesPerhaps the axis of the Buddhist section of the exhibition – a stumpant sandstone plate that shows the development of Buddha – is the most distinctive in photographing this great transition.

One sides, sculpted around 250, reveals a Buddha in a human form with complex decorations, while on the other hand – it was carved earlier in about 50-1BC – and represents a symbol across a tree, an empty throne and football effects.

The sculpture – from a sacred shrine in Amarawati (in southeastern India) – was previously part of the decorative circular base of the stop, or a Buddhist memorial.

Ms. Yansari says this shift is displayed on “one plate of one very unusual shrine.”

British Museum Secretaries

British Museum SecretariesIn the Hindu section, an early early bronze statue reflects the gradual development of sacred visual images through the depiction of the gods.

It resembles the number Yakshi – a strong primitive nature of nature that can give both “abundance and fertility, as well as death and disease” – can be identified through the floral head cover, jewelry and full shape.

But it also includes many weapons that carry specific sacred things that have become distinctive for how Hindu female gods are represented in later centuries.

British Museum Secretaries

British Museum SecretariesAlso, captivating examples of Jain’s religious art, which are largely focused on her 24 enlightened teachers called Tirthankaras.

The oldest of this representation was found on the lush pink sandstone that dates back to about 2000 years and began to be identified through the sacred symbol of an endless contract on the chest of teachers.

Ashmolian Museum, Oxford University

Ashmolian Museum, Oxford UniversityThe statues that were assigned across these religions are often manufactured in joint workshops in the ancient city of Macherma, which the curators say explain why there are similarities between them.

Unlike other offers in South Asia, the exhibition is unique because it is “the first ever” in the origins of the three religious artistic traditions together, not separately, says Ms. Yansari.

In addition, it carefully draws attention to the source of each displayed object, with brief clarifications on the object’s journey through different hands, acquiring them by museums, etc.

The show highlights interesting details, such as the fact that many donors of Buddhist art in particular were women. But he failed to answer the reason for the transformation of materials in the visual language.

“This is still a million dollar issue. Scientists are still discussing this,” says Ms. Yansari. “Unless more evidence is obtained, we will not know that. But the extraordinary prosperity of the pictorial art tells us that people have really taken the idea of imagining the divine as a human being.”

British Museum Secretaries

British Museum SecretariesThe exhibition is a multi -sensitive experience – with scents, curtains, nature sounds and vibrant colors designed to stir the atmosphere of the Hindu, Buddhist and Buddhist religious shrines.

“There is a lot of what happens in these sacred spaces, however there is calm and innate lining. I wanted to get it out,” says Ms. Yansari, who collaborated with many designers, artists and community partners to assemble.

British Museum Secretaries

British Museum SecretariesThe numbering of shows is screens that display short films to practice worshipers from both religions in Britain. This confirms the point that this is not only related to “ancient art but also live traditions” constantly related to millions of people in the United Kingdom and other parts of the world, beyond the borders of modern India.

The exhibition is derived from the South Asian Group in the British Museum with 37 loans from private lenders, museums and national and international libraries in the United Kingdom, Europe and India.

Old India: Live traditions at the British Museum, London, from May 22 to October 19.

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/adf8/live/a63473a0-474b-11f0-9471-e380f647874e.jpg

Source link